Mozambique has won backing for a landmark hydropower project, a roughly $6 billion plan to build the Mphanda Nkuwa dam and associated transmission links, a development being described as the largest electricity infrastructure initiative in southern Africa in half a century. The move is being framed as a turning point for Mozambique’s long-running effort to electrify its population, expand generation capacity at scale, and export surplus power to neighbouring countries.

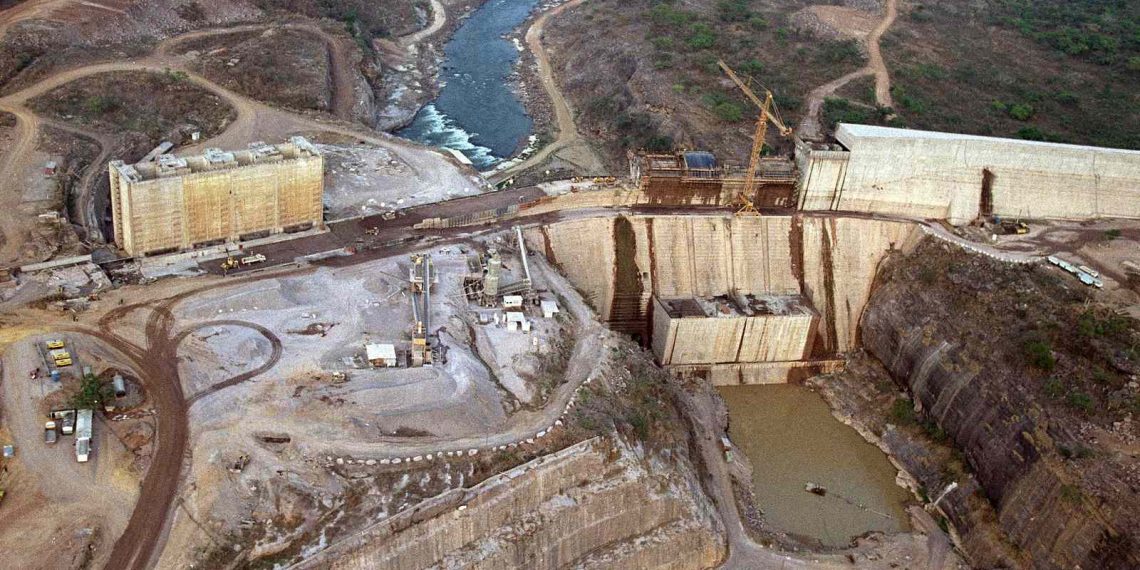

The centerpiece is the Mphanda Nkuwa hydropower scheme on the Zambezi River, a large-scale development expected to deliver roughly 1,500 megawatts of capacity and connect into Mozambique’s southern grid.

Project sponsors include major regional and international players among them Électricité de France, TotalEnergies, and the local Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa while the World Bank has pledged backing in the form of concessional support, guarantees and risk mitigation instruments to help mobilize private finance.

The scheme is reported to cost in the ballpark of $6–6.4 billion and aims for phased operation later this decade.

At scale, Mphanda Nkuwa would alter the power map of southern Africa. A 1,500 MW plant would add material bulk to a region grappling with shortfalls and aging infrastructure, enable large-scale electrification efforts within Mozambique, and create exportable surplus for countries such as Zambia, Malawi and Zimbabwe that face chronic supply gaps. The World Bank has positioned its support as part of a broader “energy for all” push that combines grid expansion and off-grid approaches to bring reliable electricity to more people.

Mozambique’s energy trajectory

Mozambique is already a major energy player in southern Africa thanks to abundant natural resources, offshore gas fields, established hydro assets (notably Cahora Bassa), and growing renewable deployments.

In recent years the country has seen real progress in household electricity access: national access rates have been reported to nearly double (from roughly 31% in 2018 to about 60% in 2024), an improvement driven by grid connections and targeted access programs. Still, large swathes of the country remain underserved, and rural electrification requires a mix of grid extension and off-grid solutions.

The hydropower push sits alongside a parallel gas story: Mozambique has moved forward with liquefied natural gas projects, such as Eni’s Coral South and the approved Coral Norte development moves that underline the country’s strategy to monetize gas while building cleaner, dispatchable power options on the grid.

Those gas revenues and projects are often cited as potential enablers for financing larger infrastructure like Mphanda Nkuwa but also as a source of political and fiscal complexity.

Benefits

Proponents argue the project will:

(a) create thousands of construction and long-term operational jobs,

(b) lower industrial power costs and attract energy-intensive investment,

(c) expand reliable household access and lift productivity, and

(d) position Mozambique as a regional electricity hub able to sell surplus power across the Southern African Power Pool.

For countries in the region that now import expensive thermal generation or rely on intermittent renewables, cheap, stable hydropower could be transformative.

Also read: The Impact of Tanzania’s Mega Projects on Regional Electricity Gap

Risks and criticisms

Large dams carry well-known environmental, social, financial and political risks. Analysts and development advocates immediately point to several concerns:

- Debt and fiscal strain: a multi-billion dollar project increases Mozambique’s exposure to contingent liabilities; careful structuring is needed to avoid unsustainable debt burdens.

- Local impacts: resettlement, fisheries disruption on the Zambezi, and downstream water rights are sensitive issues that require robust mitigation and community engagement.

- Timing and cost creep: megaprojects commonly experience overruns; commitments for transmission, guarantees and private finance must materialize on time.

- Rural versus centralized tradeoffs: while large-scale hydropower benefits urban centers and industry, rural households may need decentralized off-grid solutions to meet near-term access goals a balance must be struck.

World Bank President Ajay Banga who has publicly underscored the developmental value of electrification framed electricity as catalytic for small businesses and economic opportunity during recent visits and discussions about Mozambique’s energy push. Local utility data also points to significant household connections in the last year, although large gaps remain.

Because transmission plans include links to the southern grid, the plant is explicitly designed to produce exportable power. That opens new revenue streams for Mozambique and could relieve shortages in neighbouring systems but it also binds the project to regional market prices, transmission availability, and political agreements across borders.

Also read: Can Mozambique’s $6 Billion Mega-Dam Really Solve Southern Africa’s Power Crisis or Is It Just PR?

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the Mphanda Nkuwa Hydropower Project?

It’s a $6 billion dam planned on the Zambezi River in Mozambique. Once complete, it’s expected to generate 1,500 MW of electricity, making it Southern Africa’s largest energy project in 50 years.

2. Why is it important for Southern Africa?

The region faces severe power shortages. South Africa, Zimbabwe, and others struggle with rolling blackouts. This project could supply millions of homes and industries while boosting Mozambique’s economy through electricity exports.

3. Can one dam solve the region’s power crisis?

No. While Mphanda Nkuwa will help, Southern Africa needs much more capacity over 10,000 MW just to close the current deficit. Experts say the project should be combined with solar, wind, and decentralized energy solutions.

4. What are the risks of the project?

The biggest concerns are mounting debt for Mozambique, environmental disruption of the Zambezi River, displacement of communities, and the risk of climate-related droughts affecting water flow.

5. When will the project be completed?

Construction is expected to start in the mid-2020s, with completion projected in the early 2030s if financing and planning remain on track.

6. How does this project compare to other dams in Africa?

It’s smaller than Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam (6,000 MW) but still significant. Like other mega-dams, its success will depend on financing, management, and regional cooperation.