On September 9, Ethiopia inaugurated the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), a $5 billion megaproject on the Blue Nile that has instantly altered the geopolitics of Africa’s most important river. With an installed capacity of 5,150 megawatts, GERD is now the largest hydropower facility on the continent.

Ethiopia hails the dam as a national triumph, a development project capable of lighting millions of homes, powering factories, and exporting electricity across East Africa. But for Egypt, the launch represents an existential threat.

More than 90% of Egyptians rely on the Nile for freshwater, and Cairo has warned the United Nations that unilateral operation of the dam violates international law and endangers its survival. Sudan, meanwhile, remains caught between both sides, wary of risks but hopeful for shared benefits.

The inauguration has brought a decade-long dispute to a head, making GERD a powerful symbol of both progress and peril.

The Scale of GERD

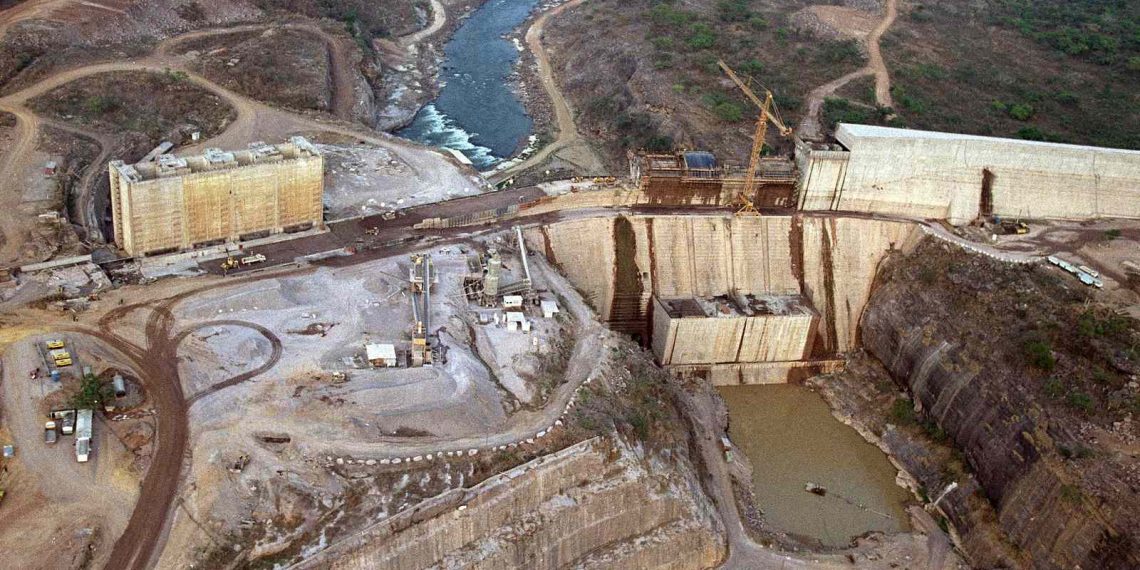

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is nothing short of colossal. It rises more than 100 meters above the Blue Nile and stretches nearly 2 kilometers across the river’s course. Behind it sits a reservoir capable of holding 74 billion cubic meters of water, creating one of the world’s largest artificial lakes.

Once fully operational, GERD will drive 13 giant turbines, generating an estimated 15,700 GWh of electricity per year, enough to double Ethiopia’s current power supply. Two turbines are already operational, feeding power to the national grid during the commissioning phase.

For Ethiopia, a country where nearly half the population lacks access to reliable electricity, the project promises a new era of industrialization and energy security. Officials also emphasize the potential to sell surplus electricity to neighbors including Sudan, Djibouti, and Kenya.

Cairo’s Fierce Opposition

While Addis Ababa frames the project as a sovereign right, Egypt views GERD as a threat to its lifeline. The Nile supplies more than 90% of Egypt’s water, sustaining both agriculture and domestic use for its 100 million citizens.

Egypt’s government argues that Ethiopia’s unilateral filling and operation of the reservoir risks reducing water flows during drought years. Officials insist that a legally binding agreement on filling schedules and annual operations is essential for Egypt’s survival.

Within hours of the inauguration, Cairo filed a protest with the UN Security Council, accusing Ethiopia of violating international treaties and warning that it will use all diplomatic and legal tools available to safeguard its water security. Egyptian media have echoed the government’s stance, framing the issue as one of national survival rather than regional cooperation.

Sudan’s Dilemma

Sudan, GERD’s immediate downstream neighbor, has shifted positions over the years. At times Khartoum has supported the project, pointing to potential benefits such as regulated water flows that could reduce flooding and enable year-round irrigation. At other times, it has expressed concern about safety, data sharing, and the possibility of uncontrolled releases that might damage Sudanese dams and farmland.

Political instability within Sudan has weakened its negotiating leverage, leaving the country in a difficult middle ground. Analysts argue that without a unified position, Sudan risks being marginalized in the dispute.

Financing and Domestic Symbolism

Unlike many large infrastructure projects in Africa, GERD was funded largely by Ethiopia itself. Construction began in 2011, financed through government bonds, local contributions, and central bank support after foreign lenders were reluctant to invest in a politically controversial project.

This financing strategy has made GERD a symbol of national pride. Ethiopian leaders frequently describe the dam as a unifying force that showcases the country’s determination to achieve development on its own terms. But critics argue that the rush to deliver political victories has deepened mistrust with downstream countries.

Hydrology, Drought, and Risk

At the core of the dispute are the uncertainties of the Nile’s flow. In normal rainfall years, Ethiopia can fill the reservoir gradually without drastically reducing downstream supplies. But during droughts, withholding water to maintain reservoir levels could cut flows precisely when Egypt and Sudan need them most.

Independent hydrologists stress that the risks can be managed if Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan agree on transparent data sharing, real-time monitoring, and emergency protocols. Without these safeguards, however, political suspicion may turn technical challenges into full-blown crises.

A Geopolitical Reality

The inauguration marks a turning point. For the first time in modern history, an upstream country Ethiopia controls a massive storage facility on the Nile. This upends the colonial-era treaties that granted Egypt and Sudan near-total control of Nile waters while excluding upstream states.

To Ethiopia, GERD represents justice: the right to harness its natural resources for development. To Egypt, it is a unilateral challenge to historical rights and survival. The competing narratives make compromise difficult, yet essential.

The immediate future will likely involve renewed diplomatic efforts. Options include:

- African Union-led negotiations with technical working groups.

- UN mediation to establish interim operating rules.

- Third-party monitoring to build trust and transparency.

- Regional power-sharing agreements, where Ethiopia sells electricity while downstream countries secure water guarantees.

If managed cooperatively, GERD could become a model of regional integration, powering homes across East Africa and regulating water flows for agriculture. If mismanaged, it risks becoming a flashpoint for conflict in one of the world’s most fragile regions.

Also read: How South Africa’s Mega-Solar Farms Are Powering a Cleaner Future

FAQs on Ethiopia’s GERD

1. What is the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD)?

It is Africa’s largest hydropower project, built on the Blue Nile in Ethiopia. With a capacity of 5,150 MW, it is designed to double Ethiopia’s electricity supply and export power to neighbors.

2. Why is Egypt opposed to GERD?

Egypt depends on the Nile for more than 90% of its freshwater. Cairo fears the dam’s operation will reduce water flows during droughts, threatening agriculture and livelihoods.

3. How does Sudan view the dam?

Sudan sees both risks and opportunities. It could benefit from regulated water flows but also faces potential threats to its dams and farmlands if there is poor coordination.

4. How was the dam financed?

Ethiopia funded most of the project domestically, using government bonds, central bank support, and citizen contributions, after foreign lenders avoided involvement.

5. Has the dam started producing electricity?

Yes. Two turbines are already operational, supplying several hundred megawatts to Ethiopia’s grid. Full commissioning will happen in stages.

6. What could reduce tensions?

Experts recommend transparent data sharing, real-time monitoring, and a legally binding agreement on filling and operation to ensure downstream water security.

7. What’s at stake for the Nile Basin?

The future of Nile geopolitics. GERD could either serve as a cornerstone for regional cooperation and energy trade or a persistent source of conflict.